Making decisions

Lecture 25

Warm-up

It’s Giving Tuesday – Give feedback!

Take 2 minutes to fill out the TA evaluation form – link in your email! Due Monday, December 8th.

Nominate a TA for the StatSci TA of the Year award by sending an email to dus@stat.duke.edu with a brief narrative for your nomination.

- Please also fill out the course evaluation (on DukeHub) as well, I’d love to your feedback!

Announcements

- HW:

- HW 5 accepted until Wed, Dec 3 at 11:59 pm without penalty

- HW 6 due at 11:59 pm on Fri, Dec 6, accepted until Sun, Dec 7 at 11:59 pm without penalty

- Final exam:

- Classroom: Half of you will take it in this room (Bio Sci 111) the other half in (Physics 128), check your email for your classroom assignment

- Review: During reading period, date/time TBA

- Office hours: TBA soon as review session is scheduled

From last time

Participate 📱💻

Which of the following is true about confidence intervals?

- They’re for a sample statistic.

- They’re for a population parameter.

- They can be either for both a sample statistic or a population parameter.

- They’re neither for a sample statistic nor a population parameter.

Scan the QR code or go to app.wooclap.com/sta199. Log in with your Duke NetID.

Why do we construct confidence intervals?

To estimate plausible values of a parameter of interest, e.g.,

- a slope (\(\beta_1\))

- a mean (\(\mu\))

- a proportion (\(p\))

- etc.

What is bootstrapping?

Bootstrapping is a statistical procedure that resamples(with replacement) a single data set to create many simulated samples.

We then use these simulated samples to quantify the uncertainty around the sample statistic we’re interested in, e.g., a slope (\(b_1\)), a mean (\(\bar{x}\)), a proportion (\(\hat{p}\)).

Setup

Computing the CI for the slope I

Calculate the observed slope:

observed_fit <- duke_forest |>

specify(price ~ area) |>

fit()

observed_fit# A tibble: 2 × 2

term estimate

<chr> <dbl>

1 intercept 116652.

2 area 159.Computing the CI for the slope II

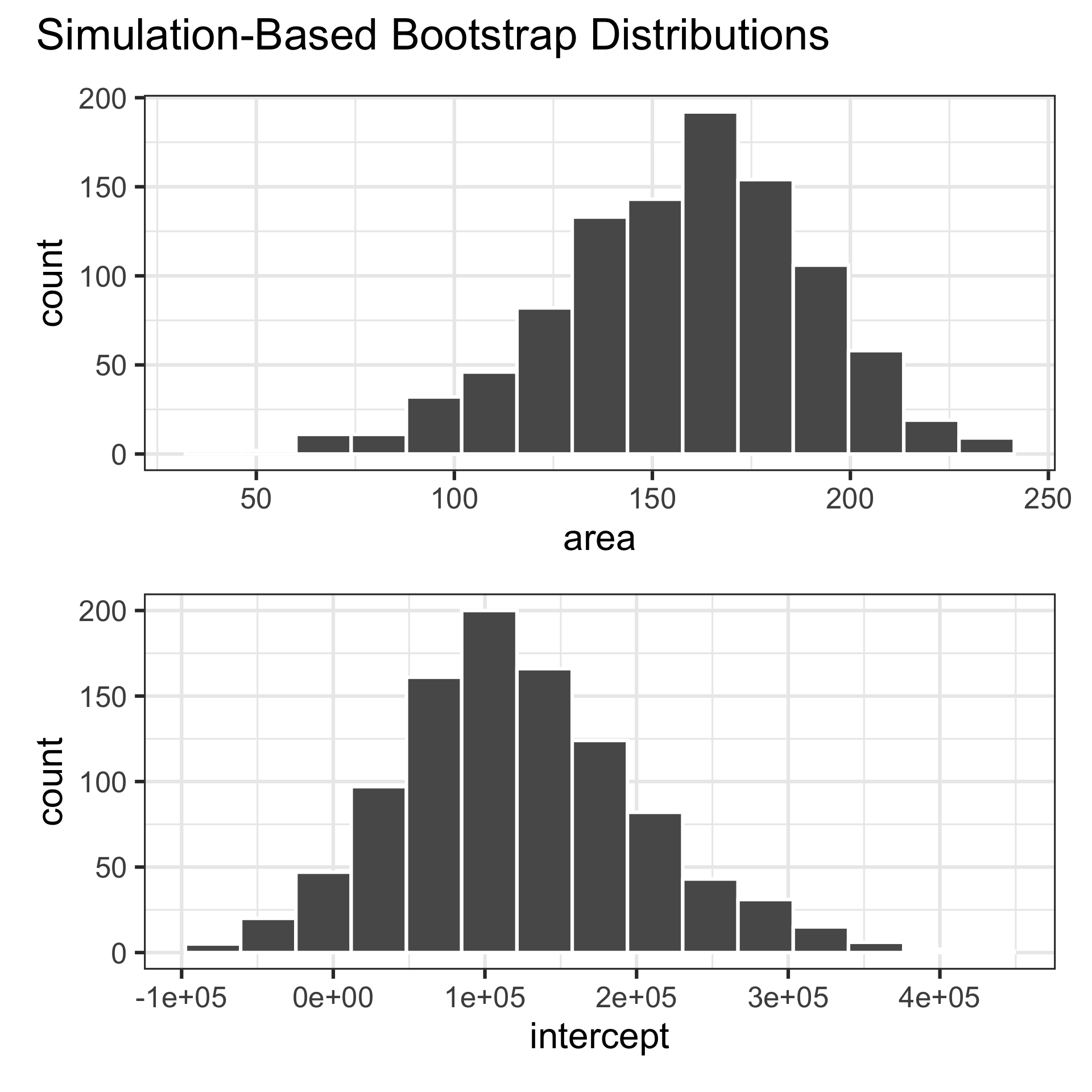

Take 1000 bootstrap samples and fit models to each one:

set.seed(1120)

boot_fits <- duke_forest |>

specify(price ~ area) |>

generate(reps = 1000, type = "bootstrap") |>

fit()

boot_fits# A tibble: 2,000 × 3

# Groups: replicate [1,000]

replicate term estimate

<int> <chr> <dbl>

1 1 intercept 47819.

2 1 area 191.

3 2 intercept 144645.

4 2 area 134.

5 3 intercept 114008.

6 3 area 161.

7 4 intercept 100639.

8 4 area 166.

9 5 intercept 215264.

10 5 area 125.

# ℹ 1,990 more rowsWhat does each observation on the plot represent?

Computing the CI for the slope III

Percentile method: Compute the 95% CI as the middle 95% of the bootstrap distribution:

Participate 📱💻

If you want to be very certain (i.e., more confident) that you capture the population parameter, should we use a wider or a narrower interval?

- Wider

- Narrower

- Depends on the situation

Scan the QR code or go to app.wooclap.com/sta199. Log in with your Duke NetID.

Precision vs. accuracy

What drawbacks are associated with using a wider interval?

. . .

Precision vs. accuracy

How can we get best of both worlds – high precision and high accuracy?

Recap

Population: Complete set of observations of whatever we are studying, e.g., people, tweets, photographs, etc. – population size = \(N\)

Sample: Subset of the population, ideally random and representative – sample size = \(n\)

Sample statistic \(\ne\) population parameter, but if the sample is good, it can be a good estimate

Statistical inference: Discipline that concerns itself with the development of procedures, methods, and theorems that allow us to extract meaning and information from data that has been generated by stochastic (random) process

We report the estimate with a confidence interval, and the width of this interval depends on the variability of sample statistics from different samples from the population

Since we can’t continue sampling from the population, we bootstrap from the one sample we have to estimate sampling variability

An alternative approach

Standard error method: Compute the 95% CI as the observed slope plus/minus ~2 * standard error (the standard deviation of the bootstrap distribution):

Margin of error

That quantity (~2 * standard error) is called the margin of error, e.g.,

On the horizon…

In this class you learned how to construct a confidence interval (i.e., calculate the margin of error) using a computational method called bootstrapping.

The bootstrap distributions you constructed (given enough

reps– repeated samples) were unimodal and symmetric around the observed statistic.This is not a happenstance! And there is theory behind it… It’s called the Central Limit Theorem!

You can learn about the Central Limit Theorem and theory-based methods for constructing confidence intervals (and other inference procedures) in future stats courses.

Syntax notes

-

Bootstrapping for categorical data

specify(response = x, success = "success level")calculate(stat = "prop")

. . .

-

Bootstrapping for other

statscalculate()documentation: infer.tidymodels.org/reference/calculate.htmlinfer pipelines: infer.tidymodels.org/articles/observed_stat_examples.html

Hypothesis testing

Hypothesis testing

A hypothesis test is a statistical technique used to evaluate competing claims using data

Null hypothesis, \(H_0\): An assumption about the population. “There is nothing going on.”

Alternative hypothesis, \(H_A\): A research question about the population. “There is something going on”.

. . .

Hypotheses are always at the population level!

Setting hypotheses

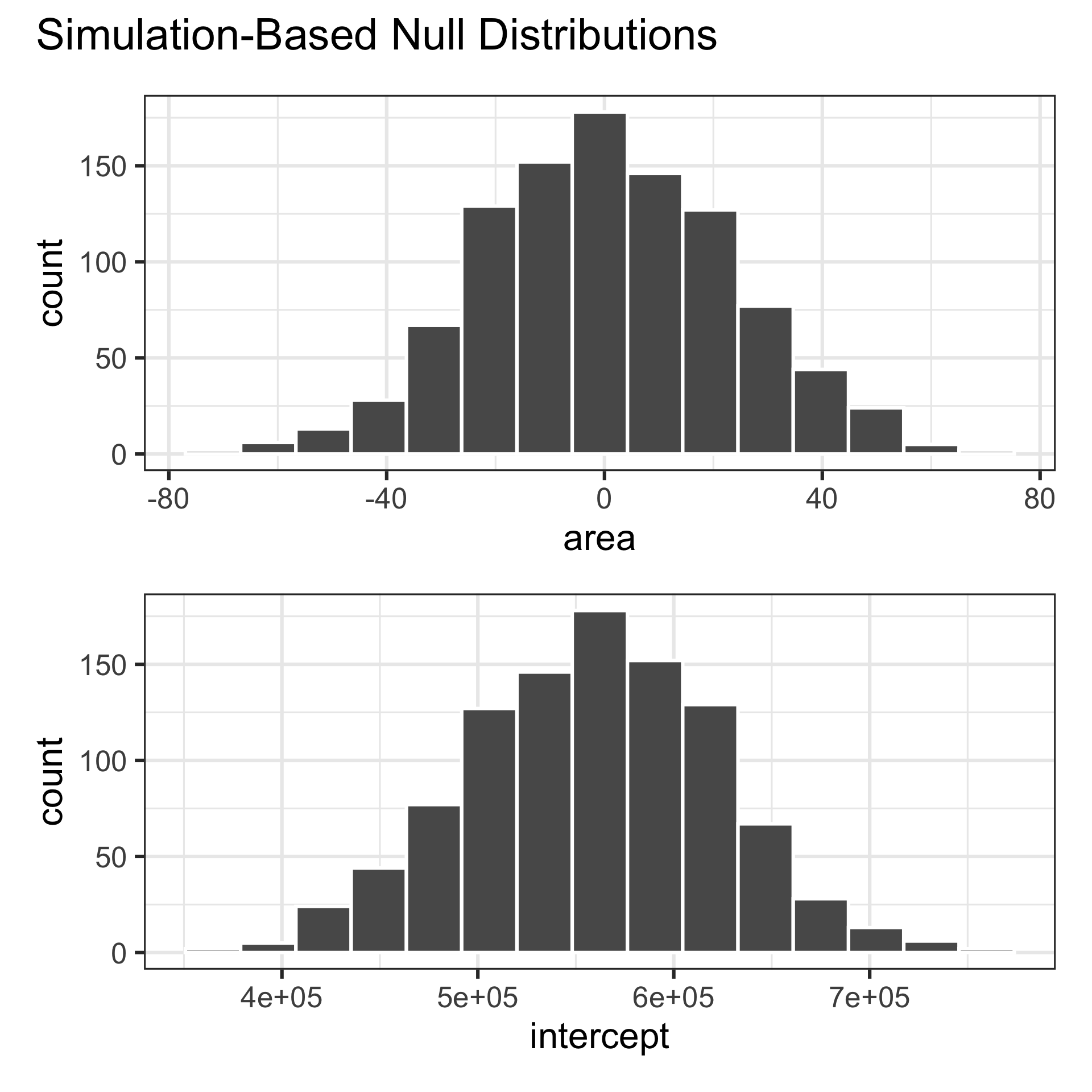

Null hypothesis, \(H_0\): “There is nothing going on.” The slope of the model for predicting the prices of houses in Duke Forest from their areas is 0, \(\beta_1 = 0\).

Alternative hypothesis, \(H_A\): “There is something going on”. The slope of the model for predicting the prices of houses in Duke Forest from their areas is different than, \(\beta_1 \ne 0\).

Hypothesis testing “mindset”

Assume you live in a world where null hypothesis is true: \(\beta_1 = 0\).

Ask yourself how likely you are to observe the sample statistic, or something even more extreme, in this world:

\[P \big( b_1 \leq -159~or~b_1 \geq 159 ~|~ \beta_1 = 0 \big)\]

Hypothesis testing as a court trial

Null hypothesis, \(H_0\): Defendant is innocent

Alternative hypothesis, \(H_A\): Defendant is guilty

. . .

- Present the evidence: Collect data

. . .

-

Judge the evidence: “Could these data plausibly have happened by chance if the null hypothesis were true?”

- Yes: Fail to reject \(H_0\)

- No: Reject \(H_0\)

Hypothesis testing framework

Start with a null hypothesis, \(H_0\), that represents the status quo

Set an alternative hypothesis, \(H_A\), that represents the research question, i.e. what we’re testing for

-

Conduct a hypothesis test under the assumption that the null hypothesis is true and calculate a p-value (probability of observed or more extreme outcome given that the null hypothesis is true)

- if the test results suggest that the data do not provide convincing evidence for the alternative hypothesis, stick with the null hypothesis

- if they do, then reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative

Calculate observed slope

… which we have already done:

observed_fit <- duke_forest |>

specify(price ~ area) |>

fit()

observed_fit# A tibble: 2 × 2

term estimate

<chr> <dbl>

1 intercept 116652.

2 area 159.Simulate null distribution

View null distribution

null_dist# A tibble: 2,000 × 3

# Groups: replicate [1,000]

replicate term estimate

<int> <chr> <dbl>

1 1 intercept 594889.

2 1 area -12.6

3 2 intercept 477930.

4 2 area 29.5

5 3 intercept 581950.

6 3 area -7.93

7 4 intercept 487542.

8 4 area 26.0

9 5 intercept 643406.

10 5 area -30.0

# ℹ 1,990 more rowsVisualize null distribution

Visualize null distribution + p-value

Get p-value

null_dist |>

get_p_value(obs_stat = observed_fit, direction = "two-sided")Warning: Please be cautious in reporting a p-value of 0. This result is an

approximation based on the number of `reps` chosen in the

`generate()` step.

ℹ See `get_p_value()` (`?infer::get_p_value()`) for more information.

Please be cautious in reporting a p-value of 0. This result is an

approximation based on the number of `reps` chosen in the

`generate()` step.

ℹ See `get_p_value()` (`?infer::get_p_value()`) for more information.# A tibble: 2 × 2

term p_value

<chr> <dbl>

1 area 0

2 intercept 0Make a decision

Based on the p-value calculated, what is the conclusion of the hypothesis test?